Sidney Lumet on "The Fugitive Kind": Delighted And Challenged

|

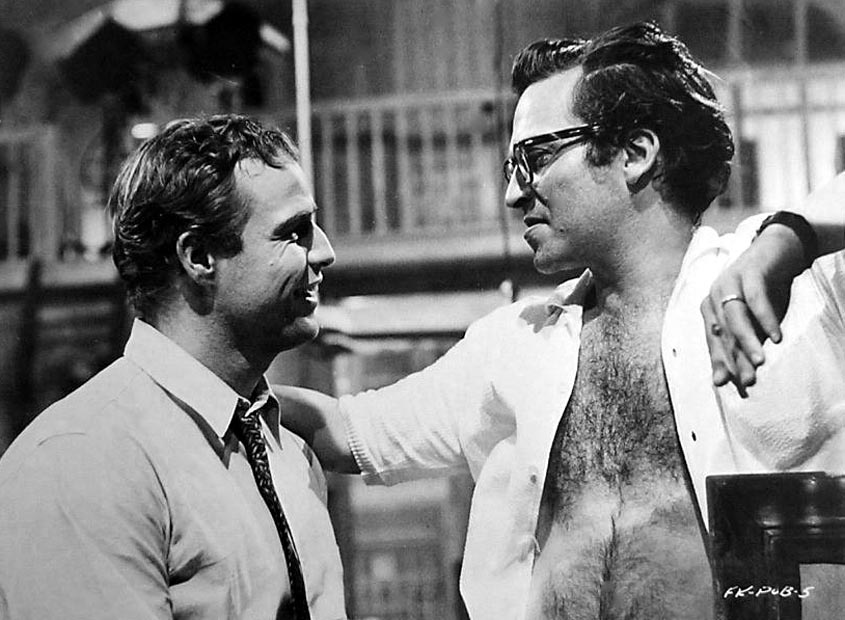

| Marlon Brando and Sidney Lumet on the set of The Fugitive Kind. |

I met Sidney Lumet at the Manhattan Theatre Club in May of 1991: We were both waiting to see Lindsay Crouse after her performance in Darrah Cloud's The Stick Wife, and he wanted to talk about the play, and he chose me and the actress Mildred Natwick to join him. At one point Natwick told Lumet about my Tennessee Williams project, and his eyes grew wide and he grabbed my shoulders. "You and I have to talk! Boy, do I have stories for you!" Phone numbers were exchanged and within days Lumet and I were talking on the phone and meeting at various intersections on Central Park West to walk and talk about various things, among them Tennessee Williams. Lumet's comments will be transformed into something--a book, an article--because his vision and his generosity were so extraordinary. Here is a small taste.

I wanted desperately to work with Tennessee, and I still regret that I was not the man chosen to direct either The Glass Menagerie or Cat on a Hot Tin Roof. I loved and studied those plays. When the opportunity arose for me to direct Orpheus Descending, which was quickly renamed The Fugitive Kind, I was delighted and challenged, because I had not responded to that play as I had the others: I still admired it; I could still remember the stunning performance Maureen [Stapleton] gave in the leading role--as the doomed Lady Torrance--but I wasn't entirely confident on my understanding of the play.

It was great to have Tennessee around on the set: He was delighted with the process of making a film, with sets, with lighting. He adored Boris Kaufman, the brilliant cinematographer, who had also been followed by Tennessee on the set of Baby Doll. Mechanics fascinated Tennessee--building a performance or a set or a sentence. He studied gestures and emotions; linens and wood; adjectives and nouns. When all the components had been put together--a scene, a set, a sentence--he would then study it for hours, talk about it, ponder it, marvel at it. I would like to think he would have made a good director, but I don't think he would have honored a deadline: He would have been looking at the same rushes for three days, marveling at his actors. He was a detail man.

Everyone in The Fugitive Kind is working out or working toward his or her salvation. It is, Tennessee kept reminding me, a play about salvation, about making amends, either with our God or with our enemies or with ourselves, and he was meticulous in allowing me to see how each character has crafted the plan of salvation. Lady wants to know love, but far more importantly, she wants to avenge the murder of her father, and she wishes to exact this revenge on her dying husband, in bed upstairs, and the man who orchestrated her father's death. Val is a dreamer, a drifter, a dabbler in all of the world's faiths and its various arts. His co-conspirator, his soul mate in a sense, is Carol Cutrere, a wild spirit, a human manifestation, like Val, of that bird in perpetual flight, constant pursuit. All of these people are doomed. Why? Because Tennessee insisted that in crafting our salvation, we are also accepting our deaths and, in a way, inviting it. The truly passionate--about meeting with God, about exacting revenge, about digging deeply into the examined life--are inviting an audience with both the darkest of life's offerings and its healing aspects. The ultimate drama, Tennessee told me, occurs in the human soul.

At that point, I felt I understood his play.

|

| Marlon Brando, Joanne Woodward, Anna Magnani, Sidney Lumet, and Boris Kaufman. |

I was afraid at first that [Anna] Magnani would look over my head and always search for the eyes of her friend Tennessee, but this was dealt with very early and beautifully: Tennessee referred to me as Mister Lumet, and he told Magnani that I was the director, a fine and sensitive man. I do believe that Tennessee and Magnani met at night and in corners to discuss the part, but Tennessee never subverted me or criticized me, and I know from others that he did not allow Magnani to denigrate me. Magnani was worried about her English, about the competition that came from Marlon [Brando], and about her looks. She was not a vain woman in the sense that she wanted to be pretty, to be looked at, but she was terrified that her Lady would not be believable as someone who could ensnare, if only briefly, someone as desirable as Val, as Brando. I did what I could with Magnani, and I adored her, but I would have to say that Tennessee accomplished more on this matter than I did. Magnani adored and trusted Tennessee.

Brando is--well, Brando is a genius. His ability to disappear within a character, and to then make this character wholly believable, is extraordinary. There have only been a handful of actors who possess the level of concentration possessed by Brando, and Magnani is one of them. If I did nothing else right, I knew to simply put these two in some tight frames and let them do their work. They make the film work--I just got the film into some cans.

I want to say one more thing about that film set, and about those people, before we go any further: The love and respect and admiration that was on that set was a lesson for me. I'm not saying that there weren't tense and unpleasant moments on that set. There were plenty of them; they occur on every set. The difference with this film is that Tennessee was often there, and Tennessee was consumed with gratitude--toward me, the cast, the crew, the world. He was already beginning to feel that his time was limited, his death was around the corner, his talents were disappearing. So he was so grateful--fulsomely so--to all of us for gathering together to make this film of his play. Tennessee also adored his actors. Joanne [Woodward] was his daughter, he told me, if he had ever had one. Joanne was smart and funny and sweet--a real divinity of a woman, as Tennessee put it. They became fast friends. Tennessee thought Marlon and Magnani had been sculpted by the gods to act, to live, to seduce, so he stared at them in awe, and was delighted to be of service to them. And Maureen was his old shoe, as he called her: the person, the heart, the soul he could so comfortably slip into and find comfort. I have seen married people, deeply in love, who did not share the level of affection and trust and care that existed between Tennessee and Maureen. Maureen had played Lady on Broadway, and she was now in a supporting role--the role of Vee--and Magnani took on the lead. Something similar had occurred when Maureen originated the role of Serafina in The Rose Tattoo on the stage, and Magnani took the role on film. Maureen didn't care. That was life, those were the breaks. Who would deny Magnani the chance to act? We didn't know if Maureen would take the supporting role, but she accepted quickly. Yes, she needed the work, but she never lacked for work. She did it for Tennessee. She showed up for her friend.

So many things are possible when there is this level of respect, this high standard toward work, this honest affection. I'm not entirely proud of the film we know now as The Fugitive Kind, but we all, I believe, were working at our highest possible standard, and we were committed to each other. We were a group, a cell, a family.

I'm proud of that.

I'm happy that I was able to give that experience to Tennessee.

|

| Magnani and Lumet. |

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comments. The moderators will try to respond to you within 24 hours.