The Violation of Marian Seldes

|

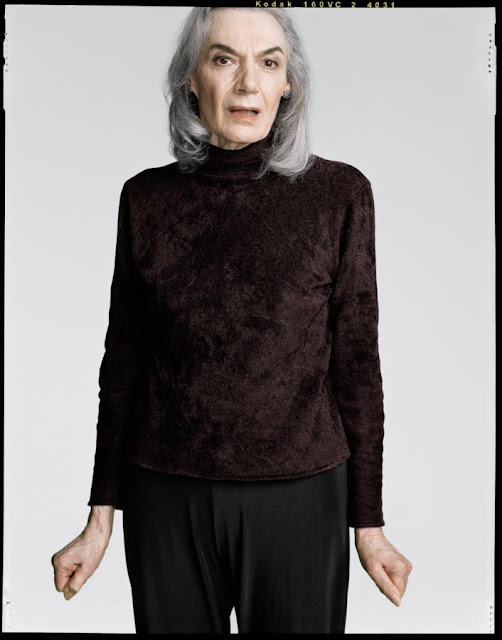

| Marian Seldes, captured by Dan Winters |

Marian Seldes waltzed through the world to a

composition only she could hear and only she could transcribe. Proudly not of

this world, she was regal and positive and ready to worship talent and people

in need and people who wanted the world to work. Marian was also an intelligent

woman, and fully aware of the performances she was giving both on and off the

stage, and she made no apologies, even as she confessed that she was frequently

teased, parodied, ridiculed. She told me once, “I guess they can make fun of

me. I’m in my own world, but my world works, and I want everyone to be in this

world, to be their best, to reach toward their dreams.”

In Rick Rodgers’ grisly, scabrous

documentary marian (the title perhaps

made so small, uncapped, because the

goal of the film is to diminish its subject), Marian is abused for nearly half

an hour, and we watch in horror as dementia overtakes her and as her avaricious

daughter laughs at the diminution of her mother and refutes the way of thinking

that sustained her. Early clips of Marian offering intelligent, honest

evaluations of herself are dark and gritty and badly lit, jumpy, amateurish,

but when we jump to the frightened, wide-eyed Marian, the images are lit as if

in a stadium, the focus sharp, and there is Marian, so often elegant and

controlled in her working years, asleep or alarmed, clearly in no condition to

offer consent for this violation. A home attendant brings her the phone and

pokes at her face as if looking for nits, and when I pointed this out to

Rodgers, his defense was that “it happened. That was real. I didn’t plan it or

tell her to do that,” a defense that I find as morally offensive as this film

itself.

What must be stated is that marian is not a film, not a documentary,

but an invasion, a protracted abuse of a woman who is not defended at any point

by those many peers and students who could let us know that her way of thinking

and living—fabulist and ornate and occasionally annoying—nonetheless led a

number of people to work and live in ways they might never have considered.

Instead, we have the talking, angry head of Katharine Andres, Marian’s daughter, her

over-plucked eyebrows like pitchforks, tightly telling us that her mother was

terrifying, that they always performed, that Marian lived to worship, while she

lives to call things as they are. If nothing else, this film will lead many to

immediately sign up for a life of denial and worship, particularly if truth, so

to speak, crafts someone like this unreliable, angry witness.

And now my disclaimers and the back story:

I met Marian Seldes in November of 1978,

when my high-school drama club spent Thanksgiving week in New York seeing plays

and musicals, and I went backstage at the Music Box, where Marian was appearing

in Ira Levin’s Deathtrap, to have her

autograph my copy of her autobiography The

Bright Lights, which had just been published. At that time I wanted to be

an actor, and Marian went out of her way to secure me an audition at Juilliard

(I had missed deadlines), and we began to speak by phone and write to each

other on a regular basis. Why? I don’t know: It was in Marian’s nature to reach

out and help people, and she often came to consider them friends. When I

eventually wrote a letter to Tennessee Williams and he agreed to meet me for

lunch in New Orleans in 1982, it was Marian to whom the playwright placed a

call, to ask if I was a good pick to entrust. Marian told him I was. When I

eventually moved to New York and to begin interviewing people on behalf of

Tennessee Williams (an assignment he had given me), Marian made calls and wrote

letters and secured interviews for me with dozens of people. She made the book

I wrote—Follies of God: Tennessee

Williams and the Women of the Fog (Knopf)—possible: She was its heart and its

guiding angel. So I am letting you know now that I am not objective in my

disdain for this noxious little film, but unlike its director and producer,

Rick Rodgers, I will clearly make my case. For those who think I cannot write

well or truly about this film, this should be where you get off.

I first became aware of Rick Rodgers when

I saw him appear with Marian in Terrence McNally’s Dedication Or the Stuff of Dreams at Primary Stages in 2005. Marian

told me he had asked if he could make a documentary about her late-life

resurgence. The film was to be called “The Third Act of Marian Seldes,” and

Marian told me “It’s about this incredible luck I have had: Marrying Garson

[Kanin], working so often and so well, having so much.” This was the assumption

of several people who agreed to be interviewed by Rodgers, and a trailer that

appeared several years ago featured their faces and their testimonies to

Marian, her unique way of thinking; her link to a theatre long gone; her

traditions; her gifts to her students. There was a lovely anecdote from

playwright John Guare, in which he related that Marian had called him to say

that Garson was unlikely to survive the night, and she wanted his final hours

to be in conversation with another playwright. Guare went to the apartment and

granted Marian her wish. That testimony is nowhere to be found in this film,

and Guare, along with Edward Albee, Nathan Lane, Tina Howe, Joe Mantello, Tony

Kushner, Elizabeth Marvel, and Terrence McNally, is a mere blip, a voiceover

lost in the shuffle of bad images and bad intentions.

|

| Nathan Lane and Marian Seldes in Terrence McNally's Dedication or The Stuff of Dreams (2005) |

After eight years of following Marian

around the city and her apartment, Rodgers has assembled a film (I use the term

loosely) that never decides what it is or what it intends to do. Regardless of

Rodgers’ intentions, the effects of the film are horrifying, and it is nothing

but a sort of snuff film poring over the face of an actress we are losing to

dementia and the greed of her daughter and her filmmaker.

Consider this: Katharine Andres, Marian’s

daughter and only child, tells us that Marian’s husband, a producer named

Julian Claman, was abusive and unfaithful and unpleasant. Marian told others

this, including Alex Witchel, who wrote a wonderful profile of Marian for the

New York Times in 2010, before Marian

descended fully into her decline. Andres castigates her mother for not seeking

help in the marriage, because to do so would be to admit that her life and her

marriage were not perfect. Andres also claims that she and Seldes left their

apartment daily in the act of performing the roles of perfect mother and

daughter. There is a legitimate charge here—a daughter recalling that reality

was a hazy concept in her life. I have no doubt that this affected her as a

child, and it clearly still rankles her as an adult. However, who is present to

offer a balancing view? Did Rodgers, who has miles of film, never discuss this

with Seldes? Why didn’t he reference the Witchel article in which Marian admits

she does not recognize the person she was in that marriage? Marian was not

oblivious to her avoidance of reality in various ways: She loved to quote Ruth

Gordon (the first wife of Garson Kanin), who often told aspiring actors given disparaging

news or facing odd effects in the mirror to “Never face facts.” Ruth Gordon,

like Marian Seldes, like Katharine Hepburn, like Tennessee Williams, crafted

her own reality that allowed her to have the career we now know and remember.

People have often ridiculed Marian for her romanticism of the past and her

refusal to face negative facts (never in my four decades of friendship with

Marian did she ever voice a criticism of her former husband or her daughter),

and they are entitled to their opinions: They could, in fact, have been in this

film voicing them, if Marian had been able to defend them, as well as various

of her students, who credit her way of thinking and exalting with bringing them

to a full creative fruition. There is none of that. Instead, we see Katharine

Andres in close-up, tight and pinched and smug, a villager from Shirley Jackson’s

“The Lottery,” her hands full of rocks, claim that Marian shook her by the

shoulders, spanked her, and withheld affection if she was disappointed in her

daughter. These comments are stated over appropriated images—distorted,

bleached—from an episode of the 1960s series East Side/West Side, in which Marian is seen coddling a daughter,

but also walking toward someone to slap them At that point, marian seems to veer toward becoming a Mommie Dearest, albeit of the Theatre

Wing, Upper West Side division. As someone who often disappointed Marian with

my cynicism or failure to believe in others, I can imagine that life with

Katharine must have been a drag and a judgment, since anger and criticism seem

to be staples of her diet. When Andres says that Marian, vacuuming the

apartment (no doubt before heading to the theatre), looks at her and says “I’m

not a maid, and you’re not a princess,” I wondered if the film might then be

about the unbalanced daughter, expecting impossible things from a parent. I

have shown this film to dozens of people and all of them can recall a similar

exchange with a parent, and none of them considered it odd or abusive, and none

of them would state it publicly about a parent, dead or living. Then I thought

the film might be about lies on the parts of both mother and daughter, but my

confusion is nothing compared to that of the filmmaker.

Rodgers claims that he strenuously worked to

create a balanced portrait, but he is either a liar or incompetent, probably

both. To have Andres spout her poisons and to then cut to an ebullient and

annoying cabaret singer yelling into Marian’s face is not a balance to the

slander. Rodgers claims that these visitors to Marian’s apartment were culled

from a list of “acceptable” people provided by Andres and Martha Wilson, an

assistant to Kanin and to Marian, and both have a lot to answer for. Rodgers

provides no information about these visitors, and they do not speak “for her,”

as he claims: They speak or shout or sing at

her, like a bad League audition or an immorally visited therapy session. A

student and friend of Marian’s visited her and considered the visit a private

privilege, valuable time with a sick mentor who had changed her life. It was

not a career moment, or something to be shared in a film or on Instagram. It

was sacred, private.

But here you can see Donald Corren, a

student of and friend to Marian, sitting close to her and three cameras, Marian’s

expressive hands touching his handsome face, struggling for words. She asks him

to sing. If Rodgers had cared more and were more diligent, he might have

learned that Corren studied at Juilliard with Marian, and that he took Marian

to Café des Artists for a dinner Marian spoke of for years. Marian rhapsodized

about his talent, his kindness, and she turned me into a fan of his work. You

won’t learn a speck of this in the film, and Corren isn’t even offered a credit

on the screen as he bonds with Seldes. Neither is Charlotte Booker, a wonderful

actress who sits with Marian and tries to remind her of words that were

important in her life: “angel” and “beautiful” and “birds,” the term of

endearment she offered her students and friends. Booker’s face is full of

empathy and caring and sadness, but did we need cameras shoved so closely and

for so long? It’s touching to see Marian fondle her pearls with wonder,

childlike, but what is being said here? Once you have established that Marian

has been lost to dementia, why is it belabored?

The worst scene is that of an actress—unskilled,

sepulchral—shouting verse into Marian’s face, and it becomes her time, an audition of sorts, a

boasting. The visiting actress comments on the scary winds, and Rodgers shoots

Marian’s still, silent face in shadows. It’s tasteless and horrifying. In fact,

there are so many shots of Marian’s eyeballs, pores, whiskers, chattering

teeth, and fingers scratching and tapping that I had to keep stopping and

re-starting the film.

Earlier shots of a functioning Seldes, shot

darkly and as if on damaged film, often capture only her voice, the camera on

an empty chair as she talks on the phone, calling people “darling” and

rhapsodizing about plans. In non-capped, pretentious titles we’ll read two thousand five or two thousand seven, as if Marguerite

Duras were in the room prepping us for the bomb (dementia) soon to follow. Why

the empty chair? The only empty chair involved in this film is the one in which

the director sat. Rodgers follows Marian about her apartment, and he features

comments about Central Park looking like a “dream,” and Marian admitting she

isn’t a good houseguest or hostess, and she only wants to get home. He seems to

be painting her as dotty. When Marian speaks of how the theatre is a healing

art and that students often grew to be beautiful or handsome through the

creation of a character, Rodgers cuts to amateurish footage he cadged while in

McNally’s Dedication, in which

Marian, as a woman dying of cancer, wore a convincing wig that conveyed a

balding pate, and the film seems soaked in urine, yellow highlights spotting the

screen. Is Rodgers punking Seldes? Refuting her claim? We’ll never know,

because, despite his claims of “balance,” he does not then cut to a student of

Marian’s –say, Kevin Kline or Laura Linney or Patti LuPone or Kevin Spacey or

Frances Conroy—who could testify to the power and truth of her sentiments. No,

we just get the Satanic daughter, grinning and laughing about her mother’s

eternal silence, while attendants shove things around Marian, who clutches a

stuffed animal and sleeps, unaware of what is being done to her.

Marian Seldes was romantic, a sentimentalist,

and it is possible a film might have been made about a mother and a daughter

who were at emotional odds: A dreamer and a realist (“I’m not worshipful,”

Andres brags) locked in a battle of beliefs; a daughter envious of the

attention and love her mother received and gave to others, but could not give

to her. There’s a story there, but it does not make to the screen with marian. I often visited with Marian, and

she had durable boxes in her apartment for virtually every production in which

she appeared. A box devoted to her first appearance on the stage—at the old

Metropolitan Opera House, in Petrushka, in

1942, contained small circles of colored paper that had been snow, photographs,

a playbill. A box devoted to Ondine,

from 1954, and starring Audrey Hepburn and directed by Alfred Lunt, contained

letters and photographs. A lot of this was cleared out by Marian’s daughter and

son-in-law, for whom Marian was a burden and an ATM machine, and incinerated or

dumped on Central Park South. Awards won by Marian have shown up on eBay and at

flea markets.

One of Marian’s final appearances in New

York is shown here—a reading at the 92nd Street Y in celebration of

Tennessee Williams on his centennial. Produced by the Provincetown Tennessee

Williams Festival, a bacchanal of non-talent and ambition, a group of unwanted "artists" who have claimed Tennessee Williams as their property, Marian appears

unkempt and shaky, not even removing her coat. Several people who were there

that evening thought she should leave, but the producers had sold tickets on

Marian’s name, so they pushed her out on the stage, where she floundered,

frightened and confused, until she is finally, after fifteen interminable

minutes, pulled from the stage. Several of Marian’s friends had urged her over

the years to not attend to the various circle jerks of non-talent, non-theatre

in the city—Food for Thought, Symphony Space—that called on her constantly,

used her up, sent her on her way. But Marian always responded to those who

needed her, so in addition to watching people plaster their ambitions all over

Marian’s apartment, we see an example of people abusing Marian through their

own paltry ambitions, even at her peril. The video of this travesty did not

appear on YouTube until several weeks after Marian’s death, and like this film,

it is a terrible memory to have of this wonderful, generous actress.

Marian believed in and loved Rick Rodgers.

She told me he was honorable and that he could be trusted. For this reason I

promoted his film-in-progress, and I offered to help him, as Marian taught me,

in any way. Then I saw the film, several times, and I had to tell him that I

could not support it, and I had to defend my friend and deride his film for the

act of abuse I think it is. Rodgers asked me to consider the time and money he

had spent on the film, and he wondered how I could sleep at night. While my

sleep is really of no concern to Rodgers, I had to tell him that my sleep would

be interrupted far more if I failed to call him out on his assault on my

friend, his exaltation of an unbalanced, rapacious daughter who dominates a

film bearing her mother’s name. I told him I thought he was honorable, but I

was wrong. Rodgers replied “You don’t know me—and you never will.” All I can be

grateful for at this point after seeing this film is that I have this promise

from Rodgers in writing.

© 2017 James Grissom

Comments

Post a Comment

Thank you for your comments. The moderators will try to respond to you within 24 hours.